What St. Patrick can teach United Methodists

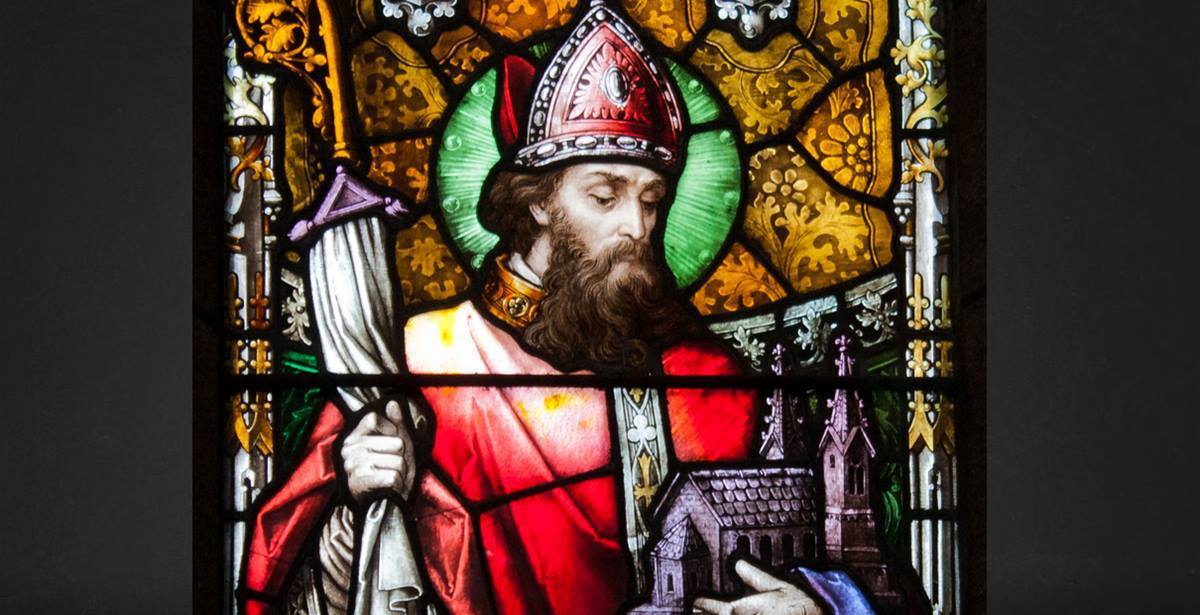

Detail of a window of St. Patric from New Ross Church of St. Mary and St. Michael, Wexford, Ireland. Photo courtesy of Andreas F. Borchert, Wikipedia Commons.

The saint Americans celebrate each March 17 was not born in Ireland, and his birth name might not even have been Patrick.

While many of the details of his life are shrouded in legend, on this scholars agree: The patron saint of Ireland left a legacy far more vibrant and lasting than the green food and beverages served on his feast day.

St. Patrick's commitment to the gospel led him at great personal risk to spread Christianity across Ireland. After his death, Irish missionaries used his methods to re-evangelize Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. When people talk about how the Irish saved civilization, Patrick had a large hand in that.

And his life and ministry offer lessons for United Methodists today.

Patrick demonstrated that "we as Christians have something worth sharing, even at great hardship," said Jim L. Papandrea, assistant professor of church history at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, a United Methodist institution outside Chicago.

"While we live in a world where we value religious tolerance, we should not let our aversion to unethical forms of proselytizing force us to go to the other extreme and completely abandon evangelism," Papandrea said.

Patrick's ministry, the professor added, is a reminder that Christ's commission to make disciples of all nations "is a form of loving our neighbor."

Snakes and pirates

The most famous story about St. Patrick - that he drove the snakes out of Ireland — has no basis in history. Scientists have found no evidence that Ireland was ever home to the slithering reptiles, aside from those found in zoos or kept as pets.

However, even without any battles with serpents, Patrick led a life that was plenty exciting. His early years read like something out of a Robert Louis Stevenson novel.

The son of a Roman imperial official in Britain, the saint who would be Patrick was born around A.D. 387, just a few years after Christianity became the official state religion of the Roman Empire. His birth name was Magonus Sucatus, according to some sources.

At about 16, he was kidnapped by Irish pirates who sold him into slavery in their native land. That was his first encounter with the island he would later transform.

Prayer, Patrick later recounted, was his main comfort during a lonely captivity tending his master's flocks. After six years, he managed to escape.

Following his sense of call to become a priest, he eventually made his way to Gaul (modern-day France), where he studied at the monastery founded by St. Martin of Tours. The future saint eventually became known as Patricius, the Latin version of Patrick.

Patrick no doubt drew inspiration from his time at the monastery, said the Rev. George Hunter III, distinguished professor of evangelism and church growth at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky.

Hunter, a United Methodist, is also the author of "The Celtic Way of Evangelism: How Christianity can reach the West ... Again."

St. Martin of Tours was an influential leader in the early church who "had demonstrated what was widely thought to be impossible," Hunter said. He started the first widespread Christian movement among the rural people of Europe, those the cosmopolitan Romans called "paganus" (meaning rustic or of the country). From that Latin word comes the English term "pagan."

Like Martin, Patrick discerned his own calling to share the gospel with pagans — but this time in Ireland.

In a dream, he heard the Irish people calling out for him to return to the land of his captivity. His bishop shared Patrick's vision with other bishops. Eventually, the pope appointed the former slave to be the first bishop of Ireland.

"As far as we know nobody in history had ever escaped from slavery and voluntarily returned to those who still owned him at great personal risk, loving them and telling them of the high God whom they had only dimly known," said Hunter. "He loved them, he cared for them and he redeemed them."

Green evangelism

Christians had some presence in Ireland before Patrick's arrival, but most were expatriates from Britain or the Roman Empire who had little interest in sharing the gospel with the natives.

Patrick helped initiate Ireland's first indigenous Christian movement, Hunter said. To do that, he adapted pagan traditions to reach new converts.

"Patrick seems to have believed that just as Jesus said he came not to destroy but to fulfill the law and the prophets, so (Jesus) comes not to destroy but to fulfill the religious aspirations of all people of the earth," Hunter said. "Patrick built on everything that he could."

For example, if people in a Druid settlement worshiped at a large standing stone, that is where Patrick and his team of missionaries placed a church. The new Christians would then carve the great stone into a cross.

He also preached in the native language, Irish Gaelic.

One popular legend is that Patrick superimposed the Christian cross on the popular Celtic ring symbol, which stood for the sun or the world, to demonstrate Jesus' redemption of the world. He thus created the Celtic cross that churches continue to use.

Another legend says that Patrick used the three-pronged leaf of the shamrock, a native Irish plant, to help teach the "three-in-one" doctrine of the Trinity.

It's not really a good analogy, even St. Patrick's fans acknowledge, since each shamrock prong does not have the fullness of the whole in the way that each of the three persons of the Trinity does.

Still, a common prayer called the "Breastplate of St. Patrick" contains some great Trinitarian theology, said Debra Dean Murphy, assistant professor of religion and Christian education at United Methodist-affiliated West Virginia Wesleyan College. The prayer likely owes at least some of its wording to Patrick himself.

"It's Trinitarian, and I think that's what can bind all Christians together - Methodist, Catholic, other Christian traditions," Murphy said. "We can have all these other disagreements, which is sort of sad that we do, but we are all Trinitarian at heart. St. Patrick can be an avenue to more grace-filled relationships among Christians."

Murphy, a lifelong United Methodist, said that prayer helped inspire her and her husband to name their son, now 20, after Ireland's most famous saint.

Great credibility

Legends about Patrick started to spread during his lifetime.

In fact, that other world-famous Irishman, Bono, has nothing on St. Patrick, Hunter said.

"He had rock star status times 10," Hunter said. "You can't buy that kind of credibility."

As John Wesley would some 1,300 years later, Patrick combined evangelical zeal with social teaching. Hunter noted that Patrick was the first well-known man in Europe to stand publicly against slavery.

But it's for his evangelism that Patrick is most often remembered. Even that famous story about the snakes may be a reference to how Patrick's ministry supplanted the serpentine symbols favored by Druids.

"Most churches assume that their main priority is taking care of the people we've got, and, of course, that job is never finished," Hunter said. But the calling to make disciples also persists.

According to the Pew Forum's U.S. Religious Landscape Survey in 2020, some 22.7 percent of U.S. adults say they are unaffiliated with any particular faith.

Like Patrick, Hunter said, today's United Methodist churches in the United States need to reach the "pagans in their own communities who are looking for life in all the wrong places."

*Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. News media contact: Heather Hahn, Nashville, Tenn., (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. This story was first published March 17, 2011.